First-in-human trial demonstrates safety, encouraging functional response in chronic phases of recovery

Targeting the cerebellar dentate nucleus with deep brain stimulation (DBS) is safe and feasible for promoting post-stroke rehabilitation, conclude investigators with the first-in-human study of the intervention. Results of the phase I study of 12 patients with persistent post-stroke upper extremity impairment were published in Nature Medicine by Cleveland Clinic researchers.

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

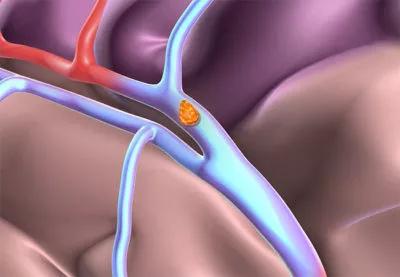

“We hypothesized that stimulating the dentatothalamocortical pathway, which connects the cerebellum and the cortex, would facilitate the reorganization of the perilesional cortex following ischemic stroke,” says co-principal investigator Andre Machado, MD, PhD, Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Neurological Institute. “Participants in this study had already undergone substantial physical therapy prior to DBS. Those who entered the study with at least a little bit of residual distal motor function showed clinically meaningful functional improvements. And there were no major complications. These results warrant further study in larger controlled trials.”

The findings build on more than a decade of preclinical work led by Dr. Machado and co-principal investigator Kenneth Baker, PhD, showing that DBS of the dentate nucleus enhanced perilesional excitability along with perilesional motor cortical reorganization and synaptogenesis.

“This study provides further supportive evidence that we can promote functional recovery following stroke by modulating the brain circuits that underly motor function,” observes Dr. Baker, a researcher with the Department of Neurosciences in Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute. “The most promising demonstration is that we can achieve this in patients who are well beyond the typical recovery window from a stroke, in this case years after the event.”

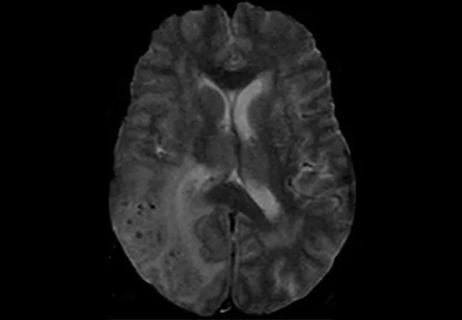

The study, known as EDEN (Electrical Stimulation of the Dentate Nucleus for Upper Extremity Hemiparesis Due to Ischemic Stroke), was a single-arm, open-label investigation conducted entirely at Cleveland Clinic. It enrolled 12 patients with chronic, moderate to severe hemiparesis of the upper extremity following unilateral middle cerebral artery stroke 12 to 36 months previously.

Mean (± SD) patient age was 57.4 ± 6.5 years. Mean time post-stroke was 2.2 ± 0.7 years. Mean baseline score on the Fugl-Meyer assessment of upper extremity function (FM-UE) was 22.9 ± 6.2.

All patients began supervised physical rehabilitation — i.e., physical and occupational therapy — prior to implantation of a DBS lead in the dentate nucleus contralateral to their stroke lesion. After implantation, patients underwent physical rehabilitation for two months followed by a month of DBS programming over several sessions.

“All patients had three months of structured rehabilitation before stimulation was turned on in order to develop a new baseline after renewed physical rehabilitation efforts,” explains Dr. Machado.

This was followed by at least four months of combined rehabilitation therapy and DBS. The study’s design allowed for extension beyond four months if patients continued to show month-over-month improvement.

All 12 patients completed the study. There were no deaths, hemorrhages, infections or other major perioperative complications. Over 168 participant-months of DBS implantation and 72 months of DBS experience, no device failures and no study-related serious adverse events were reported.

The primary measure of motor function was change in the FM-UE after DBS plus physical rehabilitation. The overall cohort demonstrated a 7-point median improvement on the FM-UE. Notably, the nine patients with partial preservation of distal motor function at enrollment (75% of the cohort) surpassed the threshold for a minimal clinically important difference in function, with a median improvement of 15 points on the FM-UE.

“This suggests that patients who have some of the neuronal pathway preserved offer us more to work with,” Dr. Machado observes. “There appear to be some surviving neural pathways that can be activated and boosted by the stimulation and physical training.”

No correlation was observed between the post-stroke interval and motor improvements associated with DBS and structured rehabilitation, with participants enrolled three years after their stroke still demonstrating substantial effects from the intervention. “This counters the expectation that time post-stroke might limit treatment-related benefit, which raises the prospect of widening the therapeutic window of opportunity for stroke survivors,” Dr. Baker notes.

In an exploratory analysis, the researchers used 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging to characterize metabolic changes across the ipsilesional cortex before and after therapy with DBS and rehabilitation. They found that patients’ robust functional gains directly correlated with cortical reorganization as demonstrated by increased ipsilesional metabolism. “These findings are consistent with our preclinical data on the effects of dentate nucleus DBS on cortical reorganization in late stages following stroke,” Dr. Baker says.

“The demonstration of safety and feasibility in this study, together with the encouraging functional improvements, supports continued study of DBS paired with physical rehabilitation in larger patient samples,” Dr. Machado says.

The next-phase clinical trial is already enrolling at Cleveland Clinic. It is a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled phase II study to evaluate treatment effectiveness more comprehensively. Enrollment will focus on post-stroke patients with at least modest residual distal function, in view of the superior response seen in this patient subgroup.

“This approach gives us a potential opportunity for much-needed improvements in rehabilitation in the chronic phases of stroke recovery,” Dr. Machado says. “The quality-of-life implications for study participants who responded to therapy have been significant.”

He notes that about half of chronic stroke patients have a residual neurological deficit severe enough to require assistance with activities of daily living, even after extensive rehabilitative training. “We clearly need a tool that enhances the effects of physical training,” he concludes. “DBS of the dentate nucleus shows encouraging promise to be such a tool. We are eager to investigate it further.”

The study was supported by The BRAIN Initiative® of the National Institutes of Health and by funding from Enspire DBS Therapy, Inc. Drs. Machado and Baker are consultants to Enspire DBS, and Dr. Machado has intellectual property licensed to Enspire DBS.

ENRICH trial marks a likely new era in ICH management

Digital subtraction angiography remains central to assessment of ‘benign’ PMSAH

Higher complete reperfusion rate seen with tenecteplase vs. alteplase in single-center study of stroke with LVO

Times to target blood pressure, CT and medication administration shorter than with EMS transport

Target: Stroke yields more frequent and faster thrombolysis, but disparities remain for non-white population

Vigilant MRI evaluation needed for prompt care of potentially reversible inflammation, study finds

IV thrombolysis should not be delayed because of planned thrombectomy

Case series demonstrates successful retreatment of this rare emergency