… of breath.You could be part of a group of individuals who experience long-term effects of COVID-19. Whether you call it long COVID, long-haul COVID or chronic COVID, the terms all mean …

… Dr. Duggal explains.What pills are used to treat COVID-19 infections?If you become infected with COVID-19, your healthcare provider may recommend specific medications that can help.Some COVID-19 medications can be …

… before getting your COVID-19 vaccine, we talked to diagnostic radiologist Laura Dean, MD.What are the COVID-19 vaccine side effects?The most common side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine include:FeverChillsMuscle achesGeneral …

… future of COVID-19 vaccination and why we should be just as concerned about up-and-coming COVID-19 variants as we’ve been in the past.Why are there so many COVID-19 variants …

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

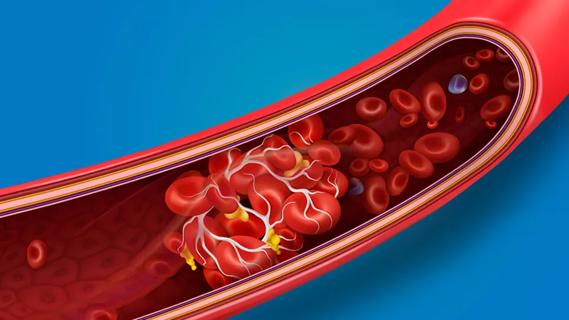

… or stroke.Research shows that blood clot risk can remain elevated for nearly a year after getting COVID-19. The risk is highest within the first week after a COVID-19 diagnosis and for those …

In the years since COVID-19 made its global debut, we’ve learned to expect the unexpected. COVID toes, COVID nails, COVID tongue: It’s wild how many different ways the virus can affect your …

… s your allergies kicking into high gear?Should you wait it out? Call a doctor? Take a COVID-19 test?All legitimate questions. And common ones. Because COVID-19, colds and allergies can sometimes feel …

For many of us, the COVID-19 pandemic seems like an event from our storied past. Gone are the days when hospitals were overwhelmed with surge after surge of the coronavirus, when we didn’t …

We all find ourselves asking these questions from time to time: Do I have allergies or am I getting sick? Am I home sick with a cold or the flu? Should I be treating my …

Now that COVID-19 has been part of our lives for several years, we’re learning more about how the virus affects the body — both in the short term and over time. But there are …

Advertisement

Advertisement