An increased risk of blood clots can last for nearly a year after a COVID-19 diagnosis

A case of COVID-19 appears to increase the risk of forming dangerous blood clots long after recovering from the infection, a cause-and-effect mechanism that could lead to a heart attack or stroke.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Research shows that blood clot risk can remain elevated for nearly a year after getting COVID-19. The risk is highest within the first week after a COVID-19 diagnosis and for those hospitalized with the illness.

So, why is this happening and who is most vulnerable? Pulmonologist Wayne Tsuang, MD, breaks down the studies and science.

Your immune system serves as your body’s first line of defense against viruses, infections and other assorted types of ickiness. If you get COVID-19, that internal security detail goes into attack mode.

That protective response from your immune system often brings inflammation. That’s typically a good thing and part of your body’s natural healing process.

But too much inflammation can become a problem. Researchers believe that high levels of inflammation in response to COVID-19 may trigger blood clots, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

The relationship between COVID-19 and blood clots has been clear since the early days of the pandemic: “We immediately saw a higher rate of blood clots in patients hospitalized with COVID-19,” says Dr. Tsuang.

Experts continue to study the connection to try to gain a better understanding of it.

Advertisement

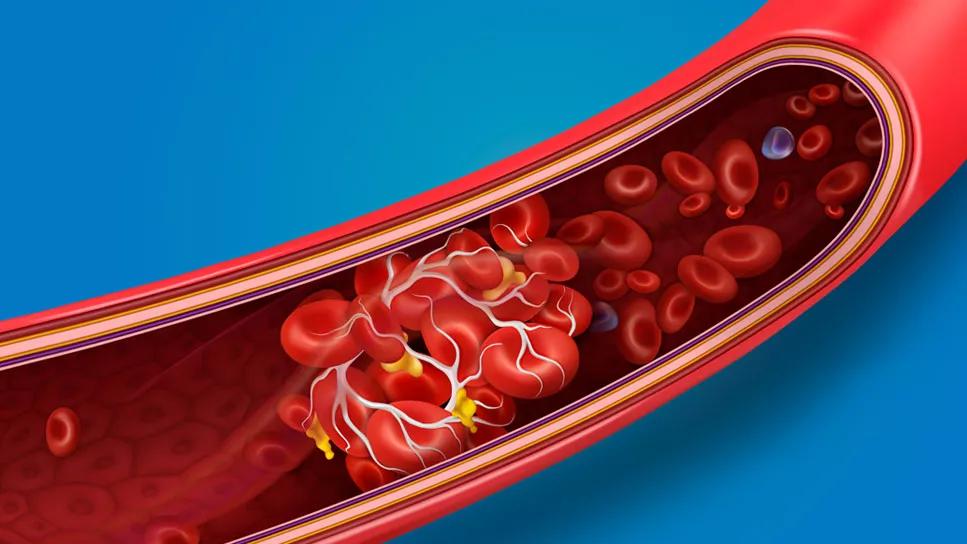

A blood clot is a clump of blood. When blood clots, it changes from a liquid to a thicker, gel-like state. That transformation is ideal when your body needs to stop bleeding (such as when you get a cut).

But clots become a concern when they break free and travel through your bloodstream. That clump of blood can block blood flow to essential organs like your lungs (causing a pulmonary embolism) or your brain (causing a stroke).

“If the clots block a blood vessel, you can lose the blood supply to that organ,” shares Dr. Tsuang.

Research shows that people hospitalized with more serious cases of COVID-19 are more likely to experience blood clots, whether in the first week of infection (when the risk is highest) or months later.

(People in the hospital also are at higher risk because they’re not moving around and circulating blood as quickly. “As blood moves more slowly, clots are more likely to form,” explains Dr. Tsuang.)

Chronic health conditions that have damaged or weakened your arteries also can increase your risk of blood clot issues from COVID-19, according to the NHLBI. Conditions that may elevate your risk include:

While a COVID-19 diagnosis increases your risk of getting a blood clot, the outcome is uncommon. One review of 1.4 million COVID-19 diagnoses showed an estimated 10,500 cases with blood clots.

Vaccinations that help reduce the severity of COVID-19 in many patients, as well as improvements in the treatment of the disease, also may have combined to decrease blood clot cases, researchers say.

Some people with the coronavirus develop a symptom called “COVID toes.” These red, swollen toes are often attributed to small clots in the blood vessels of the feet.

In the legs, swelling is the most common sign of a blood clot, says Dr. Tsuang says.

There are therapies to help prevent blood clots from forming if you have COVID-19, particularly if you’re hospitalized or have certain risk factors. Options include:

Advertisement

There’s no reason to panic about blood clots forming due to COVID-19, but it’s important to understand the risk. Talk with your healthcare provider if you have chronic conditions that may make clotting more likely.

“Ask your doctor about the best approach,” advises Dr. Tsuang. “We have strategies that can help prevent clots.”

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about our editorial process.

Advertisement

Chilblain-like skin lesions and rashes are mild (and rare) complications of many viral infections, not just COVID-19

Most can return to work or school when they’re symptom-free for 24 hours

Covering your mouth when you cough and staying home when you’re sick are a couple ways to help keep yourself and others COVID-free

This vital nutrient supports your health, but its role in COVID-19 prevention and treatment isn’t proven

Studies have shown promising results, but additional research is needed

Infection and inflammation can cause you to lose your voice and have other voice changes until you’re fully healed

A COVID-19 infection can bring on depression or anxiety months after physical symptoms go away

Just like the flu, COVID-19 continues to evolve every year with new and smarter variants

Even small moments of time outdoors can help reduce stress, boost mood and restore a sense of calm

A correct prescription helps your eyes see clearly — but as natural changes occur, you may need stronger or different eyeglasses

Both are medical emergencies, but they are very distinct events with different causes