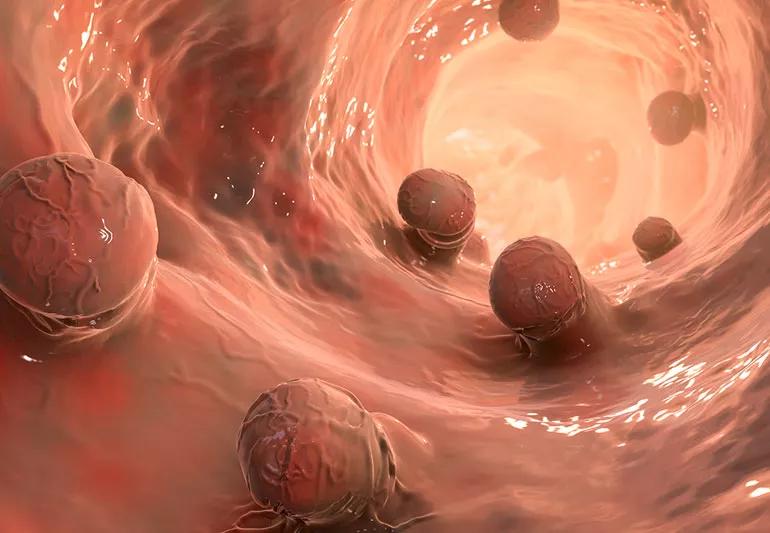

Not all polyps turn into cancer, but they should all be removed

You’ve had a colonoscopy and now hold a report detailing the results. You start reading it over and grow a little worried seeing the word “polyps” in the text. Does that mean you definitely have colorectal cancer?

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

For starters, no. The vast majority of colorectal polyps are harmless growths that sprout on the lining of your colon or rectum. They’re pretty common, especially in adults age 45 or older.

But that doesn’t mean polyps should be ignored, says colorectal surgeon Rebecca Gunter, MD. Colorectal cancer begins in polyps, after all. Finding and removing those polyps decreases your risk of developing the disease.

So, what’s the difference among polyps, and are some more worrisome than others? Dr. Gunter explains.

The smaller the polyp, the less likely it is to be on the road to cancer, says Dr. Gunter. Polyps can range in size from the less-than-5-millimeter “diminutive” category to the over-30-millimeter “giants.”

To put those sizes in perspective, a diminutive polyp is about the size of a match head. Larger polyps can be almost as big as the average person’s thumb.

Studies show that few smaller polyps are cancerous. As polyps slowly grow, however, the cancer risk rises. It’s estimated that it takes about 10 years for cancer to form into a colorectal polyp.

Polyps come in three basic shapes, says Dr. Gunter. They are:

Advertisement

Doctors examine removed polyps under a microscope for a close-up look at their cells. The review is to determine levels of dysplasia, a term used to describe how cancerous polyps appear on a cellular level.

Polyps with signs of high-grade dysplasia have disorganized cells with a larger, darker center. These dysplastic cells often grow wildly, a sign that cancer may have been close to forming in the polyp.

Your healthcare provider may recommend a follow-up colonoscopy sooner than normal if they find polyps with high-grade dysplasia. “It’s a finding that warrants increased attention,” notes Dr. Gunter.

Polyps with cells that look only mildly abnormal are labeled as having low-grade dysplasia and are of less concern.

Adenomas are polyps made from tissue that looks like the usual lining of your colon but isn’t. There are three kinds of adenomas, which doctors can determine by looking under a microscope. The types are:

Serrated polyps look like saw teeth under the microscope. They’re subtle, pale and without much form, making them easier to overlook during a colonoscopy. About 25% of colon cancers come from serrated polyps.

The answer is simple: Yes.

Though not all polyps turn into cancer, all colorectal cancers start as polyps. Removal eliminates the threat posed by a polyp. Keeping up with your colonoscopies allows your doctors to do just that.

Colonoscopies are recommended for everyone starting at age 45, or earlier if you have higher risk factors such as a family history of colon cancer. (Stool tests also are an option to screen for colon cancer, but colonoscopies remain the recommended method.)

“The reality is that colon polyps are fairly common,” says Dr. Gunter. “The good news is that removing them decreases your risk of colorectal cancer. A colonoscopy is a safe and effective procedure that could be lifesaving. Don’t delay getting it done.”

Advertisement

Learn more about our editorial process.

Advertisement

Focus on exercise, eating healthy and getting regular screenings to help lower your risk

Chronic inflammation from flare-ups can damage the lining of your intestinal wall, making your colon more vulnerable to cancer

Colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies are types of endoscopies, procedures that look at the health of your large intestine

A steady increase in cases in those younger than 50 started decades ago

If you’re at average risk, it’s recommended that you get your first colonoscopy at age 45

It’s a slow-moving process that offers an opportunity for early detection and treatment

At-home screening options can be good detection tools, but a colonoscopy remains the gold standard

Knowing your family history and getting a genetic test can help detect colorectal cancer earlier

Wearing a scarf, adjusting your outdoor activities and following your asthma treatment plan can help limit breathing problems

Your diet in the weeks, days and hours ahead of your race can power you to the finish line

When someone guilt trips you, they’re using emotionally manipulative behavior to try to get you to act a certain way