Plus, 4 factors that can make BMI misleading

Do some quick math, and BMI — or body mass index — seems like the key to unlocking mysteries about your health. But more and more people are starting to question this weight-to-height ratio. (Tom Brady, only the greatest quarterback of all time, has a BMI that puts him in the overweight range!)

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

So is BMI really accurate? Clinical psychologist Leslie Heinberg, PhD, is the director of Enterprise Weight Management for the Cleveland Clinic. In other words, she’s a weight and BMI expert. Dr. Heinberg explains the rise of BMI as a tool to measure your health — and whether to use it or lose it.

BMI measures your weight-to-height ratio. “People who are taller tend to weigh more, so you can’t compare weight without taking height into consideration,” says Dr. Heinberg. “BMI is your weight in kilograms divided by your height in meters squared.”

BMI has been around for a while. (A Belgian mathematician named Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet developed it in 1832.) Dr. Heinberg says researchers initially used BMI to describe large groups of people, not individual health.

“But it really took off around the mid-20th century with actuaries,” she says. “They were looking to describe populations to determine things like risk and life insurance.”

Looking at the BMIs of such large groups of people revealed some hard-to-ignore patterns. Certain BMI ranges were associated with greater risks of disease, mortality and other poor outcomes. And so lines were drawn — below this line, you’re “healthy”; above it, you’re “at-risk.”

Advertisement

“But it’s the same with any metric in medicine,” explains Dr. Heinberg. “Is there something magical with hypertension such that 120 over 80 is normal, and 121 over 81 is high blood pressure? No. But when we look at hundreds of thousands of people, there are differences at that line.”

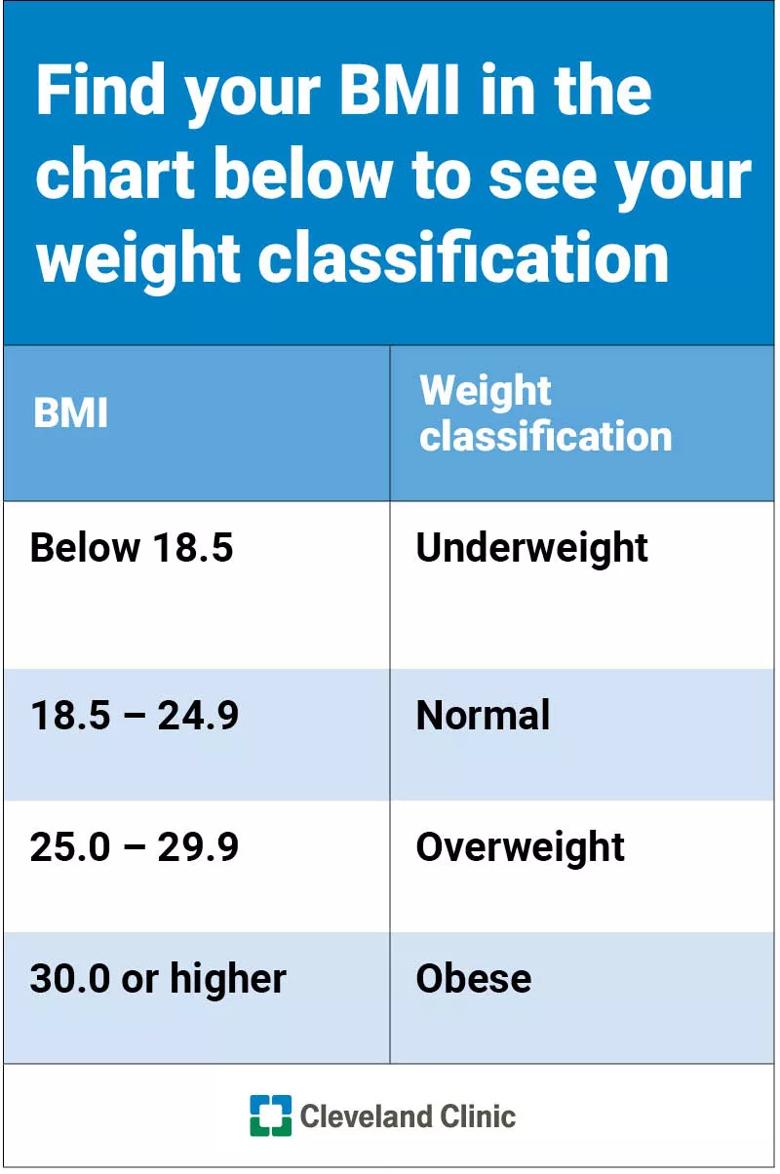

To calculate BMI, use this adult BMI calculator or these formulas:

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/64d3b021-5421-4fe4-b247-fc8a8be594fa/table-HE-BMI-weightClass_800x1204_jpg)

If you find yourself out of the normal range, Dr. Heinberg says it’s a great starting point for a talk with your physician.

“People don’t automatically need to reduce their BMI into the ‘normal range’ to see health benefits. Even dropping your BMI one or two points can significantly reduce the risk of conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

File this one under “it’s complicated.” As your BMI rises, your risk for health problems increases as well. For example, people who have BMIs in the overweight or obesity ranges are at higher risk for developing diabetes than people in the normal range.

“That risk may be twice as high,” says Dr. Heinberg. “But when you look at people whose BMIs are more than 40, the risk may increase to 20 times higher.”

BMI is an exercise in health probability. Does a high BMI mean you automatically have poor health? No. Does it dramatically increase your risk of poor health? Absolutely.

For example, not everyone who has a BMI over 40 has diabetes. But many more people with BMIs over 40 have diabetes than people in the overweight or normal weight range.

“A too-high or too-low BMI is not an ironclad guarantee that you will develop a chronic disease,” notes Dr. Heinberg. “Rather, it’s an important piece of information that you and your primary healthcare provider should look at within the context of evaluating you as a whole person.”

Some exceptions can make BMI seem more like a Magic 8 Ball, though. Factors that can make BMI not accurate include:

When it comes to BMI, people from all backgrounds are lumped together — and that can lead to unclear and confusing results. More and more research shows that there are biological and genetic differences in the relationship between weight, muscle mass and disease risk among different groups of people. BMI does not account for that.

Certain genetic factors can affect BMI accuracy because of their effect on weight distribution and muscle mass. For example, a 2011 study showed that Black women had less metabolic risk at higher BMIs than white women. Another showed that Mexican American women tend to have more body fat than white and Black women.

Advertisement

Other research shows that for people with ancestors in Asia or the Middle East descent, even a lower BMI may be misleading. They have a higher risk for metabolic diseases like diabetes at a lower BMI than people with European ancestry.

“The cutoffs we use may miss some people who are high risk and may need earlier intervention,” Dr. Heinberg notes. “They might not get the preventive care they need since they look at their lower BMI and think, ‘Great, I’m in good health, I don’t need to do anything’.”

People who are athletic tend to have a higher percentage of lean muscle mass and a lower percentage of fat mass than the average population. These factors can throw a wrench in their BMI measurements. They might measure in the overweight category (or higher) despite having great overall health.

Being pear- or apple-shaped doesn’t just affect clothing preferences. “BMI does not take waist circumference into account,” explains Dr. Heinberg. “Two people can weigh the same and, therefore, have the same BMI. But their risk for disease might not be the same.

“Say Person A has a higher waist circumference, carrying their weight in their abdomen. Person B carries their weight lower in their body. Person A has a higher risk of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, but their identical BMI doesn’t tell that story,” she notes.

Advertisement

Older adults tend to have more body fat and less muscle mass — but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Studies show that BMIs in the high-normal to overweight range may protect older adults from developing certain diseases and dying early.

Think of BMI like a puzzle piece: It’s a part of your whole health picture. Other valuable pieces include:

Advertisement

“Knowing a patient’s lean muscle mass versus fat mass may be more informative than BMI, but it’s hard to measure accurately and cheaply,” adds Dr. Heinberg. “Waist circumference is also hard to measure accurately, particularly in patients with greater obesity.

“That’s one of the reasons we rely on BMI. All you need is a scale, stadiometer (which measures height) and calculator,” she says.

Dr. Heinberg’s take-home point: Even with its many exceptions, don’t throw the BMI baby out with the bathwater.

“Blood pressure tells you about cardiovascular risk, but BMI tells you about risk for that and other conditions like cancer, endocrine disorders and sleep apnea,” says Dr. Heinberg. “Knowing someone has obesity based on BMI can lead to a more comprehensive evaluation with their doctor.”

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about our editorial process.

Advertisement

Kids’ BMI is measured in relation to others their age and sex — a healthy range is between the 5th and 84th percentile

When — and when not — to trust BMI calculators

From your ideal BMI to when to take it with a grain of salt

Having a BMI in the healthy range doesn’t mean you’re safe from health conditions often associated with obesity

This fitness plan can work as a realistic, holistic approach to a healthier you

Having underweight, having overweight and having obesity can be dangerous for your heart

Having obesity brings long-term health risks no matter your fitness level

Even small moments of time outdoors can help reduce stress, boost mood and restore a sense of calm

A correct prescription helps your eyes see clearly — but as natural changes occur, you may need stronger or different eyeglasses

Both are medical emergencies, but they are very distinct events with different causes