Learn about the challenges of racial and ethnic minority communities in accessing mental health support

Each July, organizations around the country join the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health to observe National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month. The month is dedicated to bringing attention to racial and ethnic disparities in mental health care.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

We talked with psychologist Kia-Rai Prewitt, PhD, about the unique mental health challenges faced by racial and ethnic minority communities and how you can access services.

“A lot of people don’t realize the impact of race-related stress on racial and ethnic communities. Or they aren’t thinking about some of the obstacles for people of color to access quality health services, including mental health treatment,” Dr. Prewitt says. “National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month gives us a chance to carve out some space for people to learn about the specific issues that minority populations face related to mental health.”

Research has shown that minority populations live with higher incidents of several chronic conditions. Black Americans, for example, experience higher rates of asthma, chronic liver disease, diabetes, heart disease and several other conditions, as compared with non-Hispanic white adults. Black and Hispanic communities have also experienced higher rates of severe cases of COVID-19 infection and COVID-19-related death than white communities.

A state of poor physical health can create significant stress and burden your mental health, Dr. Prewitt says.

“A lot of the health conditions we see in minority communities are from a lack of access to not just mental healthcare, but healthcare in general,” she adds. “If you can’t afford to pay for the prescriptions to manage your diabetes, for example, that can contribute to anxiety. If your quality of life has changed because you can’t manage some of your health conditions, oftentimes, that leads to depression. It’s a domino effect.”

Advertisement

About 18% of all adults in the United State live with a diagnosable mental health condition, according to the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Rates of mental health conditions are relatively similar among adults of all racial and ethnic identities.

What is strikingly different, however, are the rates at which U.S. adults get care for their mental health.

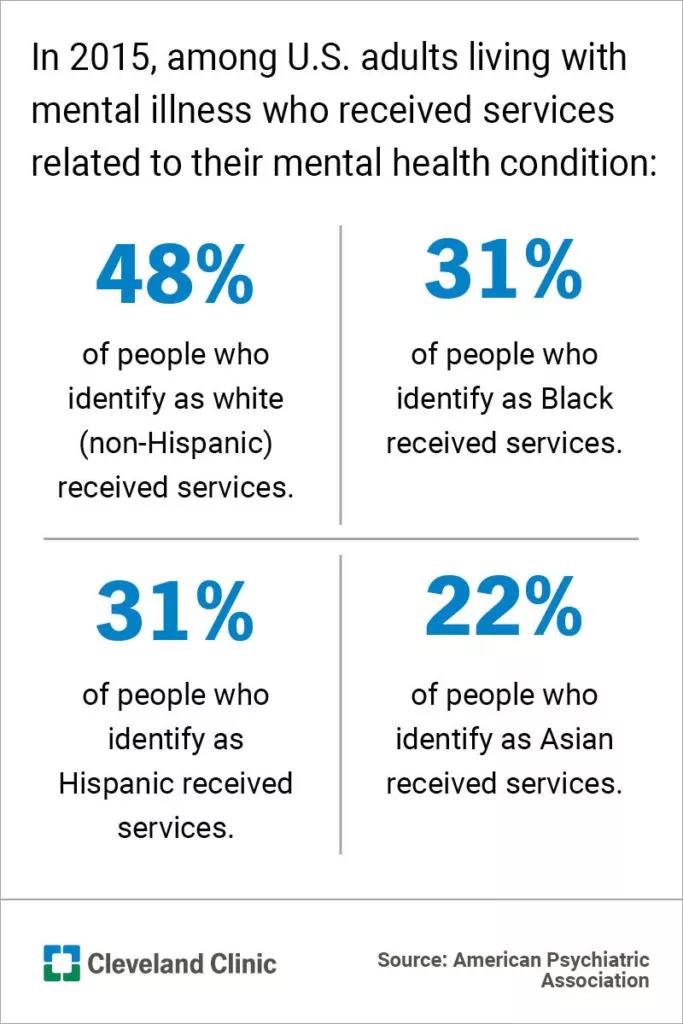

Take these statistics from 2015. APA research shows that, among U.S. adults living with mental illness:

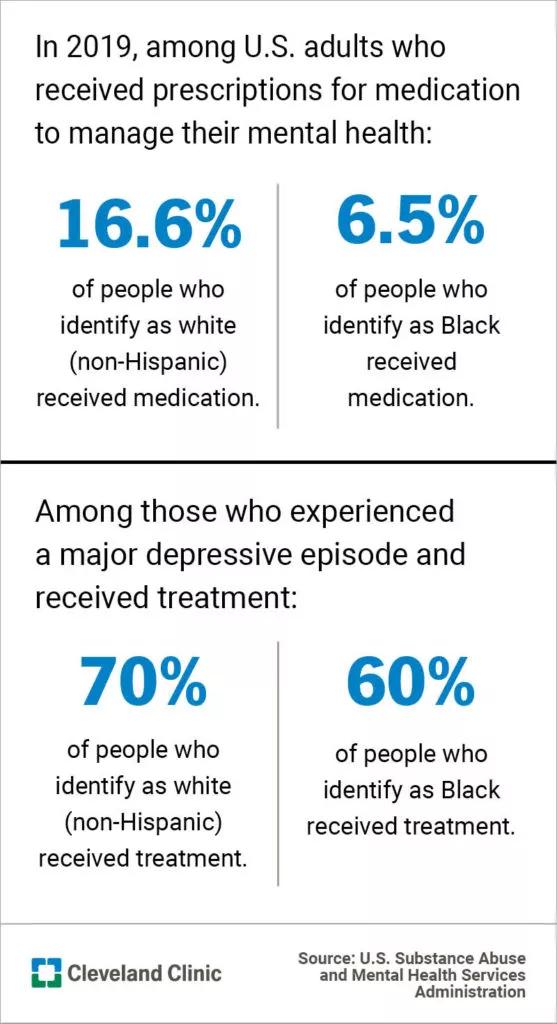

Further illustrating the disparities, a 2019 research report from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration shows 6.5% of adults who are Black received prescriptions for medication to manage their mental health conditions, compared with 16.6% of adults who are white. Among those who experienced a major depressive episode, about 60% of adults who are Black received treatment, while 70% of adults who are non-Hispanic and white received treatment.

The APA report noted several obstacles minority populations face that prevent them from getting care for a mental health disorder. Among them are:

Dr. Prewitt helps us understand a few of these barriers.

Dr. Prewitt points out that quality mental health services aren’t often located in neighborhoods that are predominantly Black or Hispanic.

“You may have heard of food deserts, where you see communities that don’t have access to nutritious foods or grocery stores. Unfortunately, it’s the same thing with mental health care,” Dr. Prewitt explains.

“Mental health resources tend to be in the communities with higher income levels, and a lot of funding for community mental health centers has, unfortunately, decreased. You find a lot of people of color who only access mental health care through the emergency room instead of being able to access regular appointments with a licensed mental health provider.”

The tides may be slowly shifting in favor of Americans becoming more comfortable with discussing and prioritizing their mental health, but stigmas are still very prevalent. Cultural norms surrounding mental health conditions can vary.

Advertisement

“A lot of people learn to keep their problems to themselves, or not to share issues in the family with other people. In some communities, there’s a stigma that if you have a mental health issue, you’re ‘crazy.’ That’s something that we often hear, and, unfortunately, that’s something that has carried over through generations,” Dr. Prewitt notes.

One way the medical community is working to address barriers that have kept minority populations from seeking appropriate care is an emphasis on training physicians in culturally competent care. Culturally competent providers and healthcare systems work to purposefully care for their patients in ways that meet their social, cultural and linguistic needs. The goal is to reduce health disparities in minority communities.

One way healthcare providers work toward this goal is by gaining training in national standards in culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS), which emphasizes care that’s respectful to the whole individual and responsive to their health needs and preferences. CLAS standards emphasize “effective, equitable, understandable and respectful care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy and other communication needs.”

Advertisement

“There is a difficult history there in terms of how doctors have provided care to minority groups, and there’s a lot of mistrust of healthcare systems in some communities,” Dr. Prewitt states. “It’s been really important for institutions and healthcare providers to provide culturally competent services. It’s something we’re talking about a lot, and it’s certainly something mental health providers and health systems see as very important.”

If you’re experiencing mental health concerns, Dr. Prewitt encourages you to seek appropriate mental healthcare. Signs to look out for include:

If you have a primary care provider, they can help you with a recommendation. If you don’t have a primary care provider, look for community resources, like clinics or support groups. You may try to look outside of your neighborhood, too, if you have means of getting there. Dr. Prewitt adds that if you have Medicare or Medicaid, you may be able to find a provider through your plan.

Advertisement

Dr. Prewitt also suggests that people experiencing mental health issues can contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (also called the National Suicide Lifeline). The national service is available to anyone needing mental health support, including those who aren’t experiencing suicidal ideation. It’s a 24/7 support network for anyone who needs emotional support.

Call 988 for free and confidential support.

Learn more about our editorial process.

Advertisement

Be cautious when others try to influence your decisions — especially if it goes against your values

When interacting with a challenging person, it’s best to lead with empathy, stay calm and set boundaries

Intention setting starts with identifying what’s truly important to you and then focusing daily on ways you can embody your core values

Using terms like ‘gaslighting,’ ‘trauma dumping’ and ‘boundaries’ in your everyday life may not be healthy or productive

Asking for help may make you feel vulnerable — but it’s actually a sign of courage

When you get bogged down with mental tasks, you can experience mood changes, sleeplessness and more

Fishing for compliments, provoking conflict and pouring on the melodrama are all ways of expressing an unmet need

Following routines, avoiding images and talking honestly, but age-appropriately, about what happened can help you and your family cope with a traumatic event

If you’re feeling short of breath, sleep can be tough — propping yourself up or sleeping on your side may help

If you fear the unknown or find yourself needing reassurance often, you may identify with this attachment style

If you’re looking to boost your gut health, it’s better to get fiber from whole foods